Issue 88: Lessons from erasure poetry

Earlier this month, a friend asked if I wanted to join her for a poetry workshop. She’d been looking for one-off writing events and found one through the NYPL website (shoutout to libraries!). We went to the Seward Park branch one warm Thursday evening, and for two hours, learned from the brilliant Bazeed, a poet and playwright, about the basics of erasure poetry. It was a small group, five of us around a basement table, and we discussed different examples before trying our own hand at writing erasure poems.

It was great to take a writing class outside of my normal genre. I’ve been deep in a novel draft for most of this year, and I recently switched focus to revising a short story for publication. Fiction isn’t a very visual medium, so I enjoyed paying attention to the aesthetic details of erasure poems. It brought me into a different headspace and awakened my attention to different textual elements.

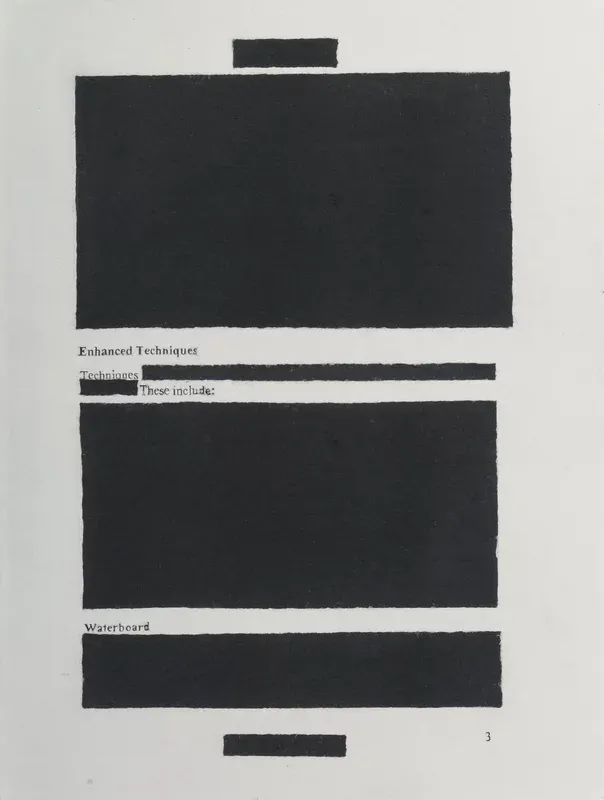

Erasure poetry is a poetic form “in which a poet blacks out or in some way erases words from a preexisting source to create new poems.” I’d previously seen Austin Kleon’s blackout poetry, but learned that there are actually many ways to approach “erasure.” Some poems have lines that are erased, like Candace Williams’ Panther Gets Loose, while others black out text, like Jenny Holzer’s Enhanced Techniques 3. In Tracy K. Smith’s Declaration, she uses dashes in her erasure of the Declaration of Independence. The dashes convey a sense of violence as they almost slash through the page, but they also serve as an invitation for readers to fill in the blanks.

Bazeed emphasized two main components of erasure poetry. The first is the textual/semantic element—the words of the poem itself and the narrative it tells. The second is the argument made through visual elements. For example, Holzer’s poem is an erasure of redacted US government documents about torture techniques employed by various agencies operating in Afghanistan and Iraq. The heavily blacked out sections mimic government redactions, leaving only the most important things highlighted. Both the header and footer are redacted, but not the page number, as that hints at there being multiple pages of what is essentially a torture handbook, a very literal example of the bureaucracy of war.

Erasure poetry can be a very powerful and political form. It’s familiar, yet disruptive. So much of it is rooted in the selection of the text and resetting it. What is the source you’ve chosen and what’s the intentionality behind your narrative? What visual and spatial elements are you working with on the page?

Here were some takeaways from this workshop and how similar concepts can apply to fiction writing:

Source documents

Source documents are crucial in erasure poetry, as they provide the language from which you will create meaning. You can’t change the documents, but you can match them to your intentions. As Bazeed told us, the question is how you can use the source document to tell a truer tale. How can you transform the original text? How can you impose your own meaning?

I think similar questions arise in fiction. Epigraphs or quotations from other sources are common in novels. Some stories are loose retellings of folktales or myths. Similar to erasure poetry, it’s important to think about how these other documents are in conversation with your work and, most importantly, the ways in which you’re using them for your own purposes.

Negative space

We spent a lot of time in the workshop talking about the impact of negative space in various poems, how they reflected the different intentionalities behind them. We examined the physical layout of the page, metadata, and visual interruptions.

In fiction, this might be literal as well, for example seeing how dialogue is rendered or varying paragraph and sentence length. In a more figurative sense, this translates to pacing, points of view, and time jumps. It’s zooming in and out on actions and emotions, drawing connections between characters and themes, and inviting readers to consider questions in what isn’t being depicted or said.

Constraints and experimentation

Our generative exercise was to all work from the same source text, the Declaration of Independence, and use it to write an erasure poem. It was cool to see how we all ended up with wildly different poems. Some of us only erased whole words, while others erased letters. Some only did one stanza, while others did more.

Bazeed described that in erasure poetry, you make your own rules and adhere to them. They also shared some examples of poets who similarly used the same canvas, but would set different rules for each erasure. One poet would return to the same source document and write a new erasure poem at different points in his life.

This issue marks four years of nicoledonut! My birthday is also this Sunday, so if you enjoy this newsletter, it would mean a lot if you donated to World Central Kitchen, which is providing emergency food relief efforts in Gaza. I’ll match up to $250 in donations (just reply to this email with a screenshot of your donation receipt). Your support means so much.

Creative resources

- The Art of Fiction with Alice Munro: “It’s not the giving up of the writing that I fear. It’s the giving up of this excitement or whatever it is that you feel that makes you write.”

- Applications are open for The Center for Fiction / Susan Kamil Emerging Writer Fellowships for New York-based early-career writers until tonight. I’ve been so grateful for all the fellowship’s resources and community, and I highly encourage anyone to apply! The application is free!

- This year’s 1000 Words of Summer starts June 1! Sign up for the newsletter here, check out the FAQ, and get the book.

- Jen Silverman on the inclination to confuse art with moral instruction: “Our books, plays, films and TV shows can do the most for us when they don’t serve as moral instruction manuals, but rather allow us to glimpse our own hidden capacities, the slippery social contracts inside which we function, and the contradictions we all contain.”

- I went down a rabbit hole of Substack essays about publishing and publishing houses, kicked off by Elle Griffin’s viral article “No one buys books”. Subsequent responses include what publishers do for authors and status resentment in the industry. I found Lincoln Michel’s roundup helpful and I continue to learn so much about the publishing business through his newsletter.

Recent reads & other media

I read two more novels for The Center for Fiction First Novel Prize. Redwood Court by DéLana R.A. Dameron is a warm coming of age story and exploration of a Black family in South Carolina in the 1990s. The Sky Was Ours by Joe Fassler is a speculative novel about the perils and promise in the pursuit of human flight.

My friend and I are reading How to End a Love Story by Yulin Kuang for our romance book club. Since Kuang is adapting several Emily Henry titles for the screen, I love that her book is about Hollywood adaptations and being in a writers’ room. Speaking of romance adaptations, of course I watched the new half season of Bridgerton, though I wish there weren’t so many competing storylines.

I saw (and loved) Challengers, which follows Zendaya, Josh O’Connor, and Mike Faist as tennis players in their athletic and romantic entanglements. The soundtrack is my new workout playlist and the script was written by none other than Justin Kuritzkes, the husband of Past Lives’ Celine Song.

E and I saw Furiosa, which I think was a very solid movie and an incredible prequel, especially considering the constraints it had to work within. Mad Max: Fury Road, one of the best action movies of the last decade, is hard to beat, but I was riveted by the more episodic character study.

Recently read short stories: “The Import” by Jai Chakrabarti, “A Madman on the Ground, A Visionary in Flight” by Joe Fassler, “Mukbang” by Divya Maniar, “Slipstream” by Ash Huang

Note: Book links are connected to my Bookshop affiliate page. If you purchase a book from there, you'll be supporting my work and local independent bookstores!

~ meme myself and i ~

“I’m going to go in the other room and read.” How I started talking to friends and family after watching Bridgerton. If Toad sang “Espresso.” Waking up to an alarm. When the argument gets heated. Little known carrot facts.